30 กันยายน 2557

On an island near Myanmar, Moken children get not only an education but a sense of pride, and are taught it's not over until the fat lady apologises. Published by Bangkok Post, Sunday Spectrum, September 28, 2014: http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/investigation/434772/the-sea-gypsies-new-flag

By Father Joe Maier, C.Ss.R.

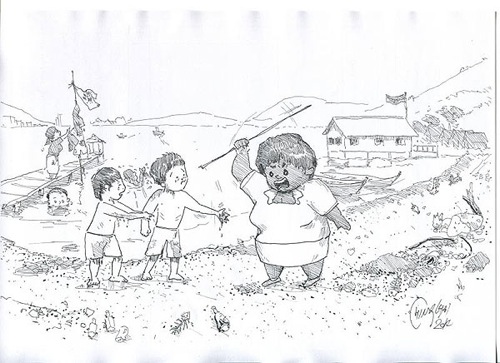

Twenty young boys and girls from the Kao Lao Moken sea gypsy camp on an island near Ranong were swimming as fast as they could. A fat lady in a long-tail boat was bearing down on them, poking at them with a stick with spines on it.

It began innocently enough, when two of the best swimmers, Nid and Nung, both eight and becoming among the first in the community to learn how to read, write and count, asked the headmistress of our school if the class could take a break and go swimming. The teacher said OK, and when they returned they began to discuss a special event.

Teacher said yes, it's Saturday when we usually have classes to "catch up", but promised this Saturday would be a special day. Birthdays and names would be celebrated, followed by a swimming contest and ice-cream. Let's make today an exception.

The incoming high tide on the Andaman Sea was perfect for swimming and the water was so clear you could see three metres, right to the bottom. And there were no jellyfish. It was not yet their season, when they might sting you, upset that you invaded their space.

This was a very special place. When the tide was low, you could walk all the way to Queen Victoria Point in Myanmar, a distance of maybe 3km, with the water mostly no deeper than your waist.

As Nid and Nung and their friends plunged into the sea, they realised they had overlooked one thing: the fat lady who operated the community's only store, near where they were swimming. She liked to give orders and was used to being obeyed. Now, with the Moken kids learning to speak Thai and read and write, she knew she was losing her power. She screamed at the swimming children in Thai and then in broken Moken: "You can't swim here!" she yelled.

Moken boys Nung and Nid were swimming underwater and when they came up for air, they heard the engine whine on the fat lady's boat. The boys knew she despised them and didn't want them to go to school. So long as they were ignorant, she had total control.

You see, before there was a school not one person on the island could count, read or write, and certainly not do simple arithmetic. It had been four years now and the children were learning, so the fat lady could no longer cheat them. Plus, now the children spoke Thai and could translate for their mums and dads from Thai to Moken.

The boys shouted in Moken: "Swim, swim back to school!"

The fat lady chased the boys in her boat as they swam, steering with one hand and trying to poke them with her bramble stick. She stabbed one boy, drew blood. Then turned to chase the others.

Some ran out of the water, up the hill and hid, still naked, behind the trees. They didn't have time to collect their clothes.

The rest — 13 of them, mostly six- and seven-year-olds, intimidated by the fat lady's cursing — stood on the wharf waiting while the fat lady struggled out of her boat, shaking her bramble stick and screaming "put out your hands". She beat the kids so hard their hands were bloody.

But cowed as they were, the children whispered to each other in Moken: "Not a word. Do not cry. Silence." And thus they kept their dignity, making the fat lady even angrier. It looked as if she wanted to hit them all again.

That's when our headmistress ran from her school along the shore to stand beside her students. She silently walked up to each child, kissed their bloody hands and made an imprint of the children's bleeding hands on her school uniform blouse. Child after child. Thirteen bloody handprints.

Then she faced the fat lady, her school blouse all stained with her students' blood, put out her own hand and the fat lady just stood there, shaking in rage. Our teacher took the bramble stick from the fat lady and cut her own hand, drew blood then made another bloody handprint on her school blouse. Then she gave the bramble stick back to the fat lady, who slunk back into her boat, started the engine and returned to her store.

Our teacher, standing on the wharf, gathered up her children and walked with them back to our school. Now that the fat lady was gone, they began crying, and she had to carry the youngest girl back. She was upset beyond walking.

The teacher first cleaned her own hand, so she could then properly clean and bandage the children's wounds, then she changed into a clean blouse and hung the bloody one in front of the school for all to see. By now, the news was spreading through the village.

And the "flag" of the Moken children, waiving in the breeze of the Andaman Sea, became not a sign of shame, but a sign of victory. And after displaying the flag, the teacher said: "Let's all have some ice-cream. We can swim some more another day."

There is no electricity on the island, so the teacher had brought ice-cream in one of those dry-ice containers from the mainland — 45 minutes by fast long-tail boat. Rumour had it that the Fat Lady sat and pouted in her store all day. Also, there were no Moken customers.

The fat lady's store is the only one on the Moken's part of the island and the children's parents all owed her money. Until now, they had never complained because they could not do the simple math, something unnecessary for living on the high seas. They had no preparation for living on the land.

The Moken had been cowed for more than 10 years now, ever since the tsunami, when everything changed. They had ended up on the mud flats of this island. There was nothing there attractive for land developers and hotel people. Once a gangster-like man came with a gun and two other thugs and waved his gun, speaking in Bangkok Thai. He claimed he owned the island and they could not live there, so they built shacks in the mud flats, a part of the Andaman Sea.

They had nowhere else to go. To fish the waters of Myanmar meant paying a large "fishing fee". Nor could they compete with the big Thai fishing boats. They could only get hired as coolies, speaking broken Thai at best. They had no resources, no language. It was pure and simple slavery.

But that was changing now. The adults still did not dare stand up to the fat lady, but that day was coming.

Nid and Nung were tasked with organising the special school event — speed swimming above and beneath the water, plus diving for treasures, just as their ancestors had done for centuries. But the children dived down only 3m, not 20m like their parents, and they were diving down to retrieve prizes given by their teacher. The prizes were cans of food, rice and fresh fruit tied tightly in plastic bags because on the island there was never enough to eat.

Besides the swimming and diving for treasure, the day was called a "group birthday" day, because none of the children knew the calendar date of their birth. Only Granny, the Moken midwife, knew. She had delivered more than 100 children over many years, including all those in the school.

Although Granny could not read or write like land folks, she did know the language of the sea. She could tell each child that they were born during the sunshine or under the moon, and also if they were born on a rising or falling tide.

They were also celebrating their own personal names. Their beloved head teacher had given names to them all. In their part of the Moken world, names early in life are not important. Only when there is a need, for example during school registration or when sick and going to the big hospital on the mainland, did they need a name.

The headmistress is the most trusted person on the island, so she became the giver of names. When a new child came to the kindergarten and needed a name, at least for the sake of convenience, she would first ask the child if they liked any special name, then would consult with the parents for a meaningful Thai name.

Something of the sea or the island — like the name of a beautiful bird or fish or even a beautiful sky or sunrise. The local shaman was consulted, too, of course.

The next morning, after roll call, the fat lady came to the porch outside the school. The head teacher would not allow her in and the three dogs who lived there growled. The fat lady asked that they take down the blouse stained with the children's and teacher's blood. Our teacher asked the children what they thought. They said the fat lady had to apologise.

The fat lady mumbled some words, but that was enough. Also, she brought candy from her store, but the children refused to take it and told her to take it back. No one could buy them off.

That very afternoon, as school was closing, all the villagers came to the school and individually thanked their children's teacher. They said their precious Moken blood had mingled with her Thai blood and now she was a Moken sea gypsy too, or as close as anyone could ever get.

The shaman said our teacher would always be protected. The spirits of their ancestors and the spirits of the sea would be with her no matter where her path in life led her.