The Way We Fight Back In Klong Toey

11 April 2011

By Father Joe Maier, C.Ss.R.

Published, Bangkok Post, April 10, 2011

Violence and mayhem don’t just happen in our slums. It’s not how we handle our affairs. When it does, it’s almost always from outside causes.

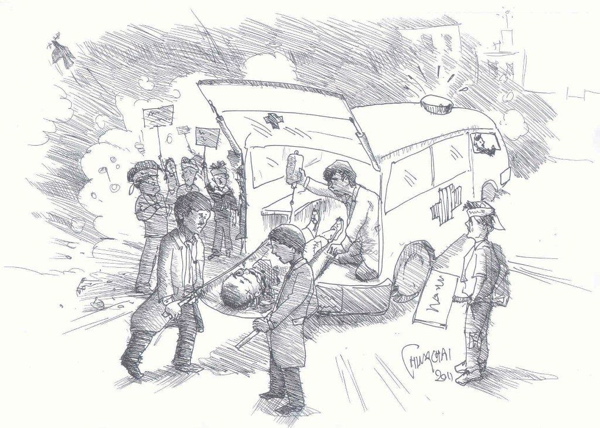

This was the case for Klong Toey's Khun Dhee, whose life descended into mayhem during the red shirt demonstrations two years ago

He was hit by shrapnel from an old tear-gas canister during a fracas. Its effects are insidious: you can't breathe; smoke sears your lungs, your eyes, the chemicals mixed in with the shrapnel burns deep to scar, maim and cause wounds that won't heal.

Dhee, an artist and portrait painter in Klong Toey bore the entire vicious brunt of the tear-gas grenade. Shrapnel tore his right lung, bruised and cracked some ribs, breaking one, and mangled his right hand. A couple of pieces of shrapnel penetrated his chest and throat, bringing him to his knees.

He kept his head back to make it easier to breathe and clasped his good hand to his throat, trying to ease the pain. He never lost consciousness during those first few minutes and kept a tight grip on his motorcycle key with a sacred image attached.

Later, eyes swollen from the searing tear-gas, all he could think of was his wife Mam and his sons, Blue and Jazz, waiting for him at home. He didn't know how badly he was wounded, and thought he could still manage to ride his motorbike.

Dhee married Mam 13 years ago, and before marriage they had a 9 year courtship. In those 13 years, they had not been apart for a single night. When he didn't come home and didn't phone, Mam feared the worst.

Our old friend Mr Mah, head of the Klong Toey Emergency Relief team ambulance service, was just a stone's throw away from where Dhee was hit. He heard the gunfire, saw the exploding canisters and was blinded a bit by the gas.

As Dhee lay wounded, folks gathered around him - red shirts, yellow shirts, men in uniform, all briefly united, everyone shouting to hurry up, to get Dee to a hospital. Everyone shouting for Dee not to die. People from all groups promised to pay his hospital bills, no matter what. Everyone wanted to touch the wounded semiconscious Dhee to give him the strength and courage to survive as they loaded him into the ambulance.

Mah (a nickname meaning "loyal, protective dog") had someone else drive while he cradled Dhee in his arms, holding his head with his hand so that the wounded artist could breathe.

"Dhee, you're going to be OK. You're safe," Mah said. "You know me; I used to buy noodles from your dad's shop in Klong Toey. I used to take you to school sometimes."

And Dhee scribbled one word on a bloody piece of paper with his left hand: “Mam.”

"Just please try to keep breathing," Mah said. "I'll get you home."

Twenty minutes later they had arrived at the emergency room of the nearest hospital.

Mah had phoned ahead, but the hospitals were already on red alert. (They took him to the very hospital he’d visited that same morning when visiting the wounded – those wounded on the same streets.)

Thirteen hours in surgery. Khun Dee lived. The surgery team later joked in gallows humor how they cried their eyes out as they “repaired” him. But it wasn’t from sorrow; he reeked of tear gas.

He was to be in the hospital for two-and-a-half months and eight more operations.

He’s now back home in the flats in Klong Toey, living with his wife and his sons, Blue and Jazz, still drawing, still painting portraits perhaps just as good as before, maybe better, but surely slower now with his left hand.

He had always been a right-handed artist.

He began re-learning to draw a full month after he left intensive care, with armed men waiting outside his door. Then, in a room of his own, still in hospital, he picked up a pencil and began drawing. With his wife patiently sitting beside him, helping him, it took him the next three months, 16 hours a day, to learn to draw with his left hand.

Slowly, the miracle happened: his left-hand drawings were becoming as beautiful as his right-handed ones had been before.

Dee’s been a stubbornly hard worker all his life, even as a little kid. Selling flower garlands on slum street corners. Working as a “bus boy” on the old red clunkity-clunk Klong Toey Baht busses. He became a novice monk at 9 years old for a month to make merit for mom when she died. Dropped out of school after that - in the 3rd grade - to help his dad set up their two-tables-and-six-chair street corner noodle shop, open nightly, 6pm to 10pm. Dad, born in mainland China, always smoking and coughing, wasn’t that strong anymore.

At nine years old, Dee was a nighttime noodle-shop helper with dad and a daytime kid coolie in the Klong Toey Port: a go-for-this-go-for-that errand boy, running up and down gang planks of the cargo ships. Whatever any of the men or women wanted, he got for them. Quick service. Cash up front of course.

That's when he first started drawing. He'd draw with the stub of any pencil on any scrap of paper he could find. Then one of the men at the port bought him a pad of drawing paper and a couple of pencils, and Dhee was on his way, drawing everything he saw, learning to illustrate, shade, add texture, create art. It changed his life. That's why he was there during Bangkok's troubles and had his right hand blown off - to tell at least some of the story in sketches.

Back when he was nine, he started sketching portraits of the men at the port working - loading and unloading ships, sitting, eating, talking, playing cards, everything, all the everyday life. They’d give him maybe 10 or 15 Baht for the portraits, depending if they had any money. And Dhee’d give the money to his dad.

But back to that night of violence and mayhem. I haven't told you yet about how Mam found out about Dhee. It wasn't cool. When he didn't come home, she panicked and started phoning all of his artist friends who might have been with him.

Nobody knew anything.

Then came a phone call. Someone's girlfriend had just seen a news flash in England and called long distance to Thailand. Her artist boyfriend was Dhee's friend. She told her boyfriend that she saw Dhee wounded, being loaded into an ambulance. The boyfriend called Mam, and Mam found the hospital.

At first, staff at the hospital reception were cautious. She was his wife? After a battery of questions, they finally said, "Yes, fine, but he's still in surgery." She was there when he regained consciousness.

A real shock came with the next morning’s Thai newspapers. Dhee was on the front page, and pointing to his mangled hand holding a key, the newspaper suggested that his own bomb had gone off before he could toss it. Painting him as a terrorist, his injuries were of no great loss: good riddance to bad rubbish.

But he wasn't holding the key to a bomb. It was his motorcycle key with a sacred image.

Mah, who took him to hospital, and the team of surgeons who operated on him, later testified that in his clasped fist were a motorcycle key and a sacred image on a key chain. He also had a mobile phone hanging from a cord around his neck, blown to pieces by the shrapnel, that most surely protected him from more chest wounds.

The papers later apologised. Dhee never took them to court for defamation.

He said the Thai equivalent of that old motto: "Least said, soonest mended."

We in Klong Toey rarely kill each other.

We govern ourselves as we have since the old days: Klong Toey justice. The first resort is a bottle of local whiskey, ice and soda and hours of street corner horse trading. What is said in a Klong Toey street corner whiskey and horse-trading session stays there. Not spoken of again. In most matters, this kind of problem-solving can be much more effective than in police stations and law courts.

Dhee, now 45, lives a quiet life, but remains busy as an artist in the flats. His boys are now eight and 10. His wife Mam looks after the family, while Dhee works steadily at the drawing table in their flat.

In many wonderful ways, Dhee is the essence of Klong Toey, where beggars are also poets and bag ladies sing songs of life and the music between Earth and sky. A place full of mothers and grandmothers, where children are still mostly safe. Klong Toey, a place, really, where the people who play music on street corners and draw pictures and paintings on the pavements of cities around the world would like to experience. A place of no polish, no refinement, where the language is colourful and you don't need to wash your ears.

Dhee is there in the flats. Yes, along with a few rats and cockroaches, but they have their place too.

One final note: Khun Dhee is the talented artist who has been illustrating my stories for the Bangkok Post for several years. It is his illustration that accompanies this one.