Honour Thy Parents, a Lesson Learned Too Late in Klong Toey

28 May 2012

Old-time protection against guns and knives can be engraved on to the skin, but as 'Uncle' found out, even the shaman's best inks are powerless against the pain of shame and lost loved ones

By Father Joe Maier, C.Ss.R.

He doesn't wear amulets, but says his tattoos are the best on the planet. Amulets, nowadays, can be fake, or even worse – not even blessed, no power. You can't be too careful. So tattoos are safer. His Chinese dad told him that long ago.

And Uncle Mongkhol's tattoos are real, no doubt about that. Thumb-nail size on each shoulder and barely legible, faded by time. But ancient beliefs say that a khom tattoo does not lose power or potency through the years. Both tattoos are letters written in Khmer script, signifying ''mother'' on one shoulder and ''father'' on the other. Uncle says quite piously that the letters are to remember his beloved parents. No doubt about that, but not quite so piously, a khom tattoo from years gone by is comparable to the awesome Gaw Yawd (Nine-Pagoda Peak), strongest of all tattoos for those who live by the gun and the knife.

Old-time protection and healing for both police and gangsters against lethal gunshots or knife wounds, together with a sachet of sacred blessed herbs (worn around your neck), which you swallow immediately if wounded, either by gun or knife. These herbs are expensive and most difficult to obtain. Plus, you must believe. Trust the potency of the herbs together with the spiritual strength of the shaman who bestowed them upon you.

Protection? Yes. But from sorrows of the heart? No.To make a long story short, he was 17 when he ran away. Wanted to be a ''fix-it'' man. His parents had a restaurant on a raft moored to the riverbank. He wouldn't work in the restaurant, and wouldn't go to church on Sunday with mum. Stopped saying his prayers. ''That's for little kids and old ladies!'' he said. One day he drank some whiskey, stole money from the restaurant and fled to Bangkok.

Mum and dad said, ''You speak two Chinese languages and you graduated top of your class in that expensive private school we sent you to. You shall not associate with 'fix-it' people. You shall continue your education. You shall meet fellow students born of respectable families with important business connections for the future. Also, you might meet a girl who, well ... is not poor, who speaks Chinese. How can we find you a proper wife if you are a 'fix-it' person?'' But he didn'’t hear what they were saying.

In Bangkok he wandered the streets, hungry and alone. Then remembered a tao gae in the Klong Toey slaughterhouse, who knew his dad. Lucky, really. Mongkhol went to beg for a job. Any job. The tao gae travelled up-country frequently, buying pigs from villages by the river. Whenever he could, he stopped at Mongkhol's dad's raft, and had a glass of local home brewed coffee with a glass of tea for a chaser, with two soft boiled eggs in a glass and two deep-fried Chinese rolls with sweet condensed milk.

He recognised young Mongkhol and listened to his story. True, he wasn't strictly ''family,” but he was close enough. The tao gae hired him to work in the pigpens of Klong Toey slaughterhouse.

Mongkhol didn't know it at the time, but he had ''come home''.

The tao gae trusted him. Soon, he was the long ju – the second man in charge of overseeing about 40 pigs a day. All transactions are in cash, and cash brings danger. The tao gae wanted to protect his investment in Mongkhol, and that's what brought on the tattoos.

The tao gae (who had his own tattoos) brought him to pay respect to an elderly Cambodian shaman who was revered in those circles. He blessed the ink, blessed the silver pens, and prayed over Mongkhol. After ritual bathing, fasting and mediation, the shaman invoked the winds from of the four points of the Earth, and he breathed over Mongkhol. Then he ritually traced the khom tattoos so that he would be safe from danger.

The shaman lived under a grove of sacred trees near the Klong Toey Temple, built long ago on the canal next to the slaughterhouse. The temple was famed as a refuge for those avoiding the law. Paying your dues back to society by regular prayer and meditation living in a temple is a lot better than maximum security prison.

Mongkhol worked several years in the slaughterhouse. Made 100 baht a month – good wages in those days. But he never forgave himself for running away. For stealing the money. For embarrassing his parents. No tattoos could protect him from that. He went back to visit the raft restaurant often enough, begged dad's forgiveness, promised mum he would say his daily prayers, go back to church for Christmas and the yearly church feast and blessing of the cemetery. But Mum and dad would never talk about it. Ever.

Mongkhol lost his own wife and children. He met his wife in Bangkok. They had a three-year-old boy and she was pregnant. True to his promise to mum, he came home for the yearly church feast and brought his wife.

But mum never approved of her. Clucked her tongue and said: ''This will never work. She's a foreigner and she doesn't speak Chinese, can't cook our type of food.'' His wife tried to help out, but didn't quite know what to do in their restaurant raft and couldn't please mum. After the church feast, they hurried back to Bangkok. Mongkhol's wife said she would never, ever come back.

The marriage failed not much later.

It went down like this: Mum and dad were old, and the bamboo restaurant was pretty much yesterday's news. Mongkhol, their only son, began visiting more often.

He had the restaurant raft repaired, and his wife complained about the money. Said he was stupid, and that it should be open at night for karaoke, maybe have a band and a couple of young girls to serve drinks. His parents were horrified.

Mongkhol said to his wife: ''Let's keep the restaurant as it is. There are enough customers. Let's stay a while, and dad can teach proper Chinese to our son. You can learn how to cook good Chinese food.'' She refused. If she was going to care for anyone's parents, it would be for her own.

She bolted, heavily pregnant, and took their three-year-old son. Stole their money, just as Mongkhol had stolen his own father's money so many years before.

He said the night before she left, he felt his tattoos hurt, and he couldn't sleep. They were warning him, but once again in his life, he didn't listen.

She took the money and caught a bus to her relatives' home in the provinces. Mongkhol heard rumours that, not long afterward, when the money was gone, she had ''farmed out'' the two children with neighbours and she had been hired as a maid, ''or whatever'', in Saudi Arabia. And that she returned some years later and married a man in the Northeast. Anyway, Mongkhol has never seen her nor their children again.

His dad had once said to him: ''My son, my only son, promise me by those tattoos on your shoulders and all else you hold sacred that, no matter what, you won't let your children grow up alone without you''. But Mongkhol had failed. He didn't keep his promise to his dad.

When mum and dad died Mongkhol took care of the religious rites. Funeral mass for mum, buried her in the cemetery of the Catholic village where she was born. Buried her next to her own mum and dad, so that she wouldn't be alone. Cremation for dad, took his body to the temple near the sacred grove where he received his tattoos, then he went back to the food shop. Placed dad's ashes in the river, upstream from the raft. Dad had always wanted to make one trip home to China. And that never happened. But Mongkhol said the best he could do was put his ashes in the river that brought him to Thailand so many years ago.

Then Mongkhol sold the raft and went to sea, hired on as a ''fix it'' man on an oil tanker plying between Singapore and Bangkok. After finishing his contract on the tanker, he didn't know where to go. He thought of that sacred grove of trees where the old shaman gave him his tattoos. And when he did, he knew there was a place for him somewhere in Klong Toey.

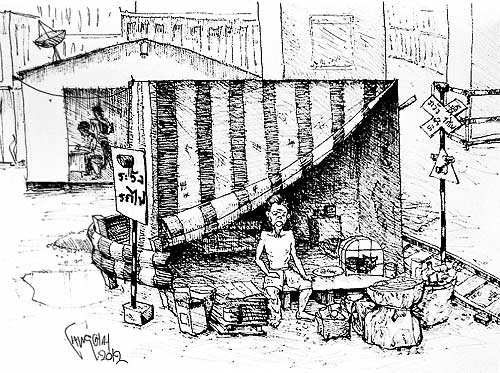

Now Uncle lives on the platform of one of the pillars of the expressway. His ''almost a shack'' doesn't have proper house registration. True, he doesn't have anyone to send him mail, but if he did, well, the postman knows him and the letter would arrive safely.

Neighbours bring him collectables – anything thrown away, or left outside unwatched that might have some value – and he sells them to the junk man. Gets top price because he is known and respected. That gives him a bit of spending money, and each morning, with his walking stick, he walks to the nearby restaurant under the expressway, where at night there is karaoke singing and at daybreak there is home-brewed coffee with a glass of tea as a chaser and two soft boiled eggs in a glass with Chinese deep-fried rolls. Prices have gone up but the owner still charges him 10 baht.

He says he's sad he's never seen his own children again, and has no one to call him ''dad'' or ''papa'', or to teach to read Chinese; but everyone calls him Uncle, and he says that's good enough for now.